I think there is a column waiting to be written about the youngsters in San Antonio who were in similar straits during the polio shutdown of the late 1940s and are now the great-grandparents of the youngsters currently shut down (because of the COVID-19 pandemic). Everyone over 75 who has lived his or her life in San Antonio has a story to tell their great-grandchildren that the scourge of their childhood was polio, which was most concerning because children were left crippled. (There were) no theaters (open), no school, no funerals. Now 70 years later, these great-grandparents are again the target population for the worst outcomes. It would also be reassuring for today's youngsters to know that their great-grandparents rejoiced and rushed to give their grandparents the polio vaccine almost 10 years later; and with so many working to produce a vaccine for the coronavirus they should not have to wait that long.

— Pat Larsen

I was about 9 years old when the polio epidemic hit San Antonio in 1946. All I remember is that everything was shut down except grocery stores and hospitals. Can you find and give us all the details about this epidemic, how it was handled and how long it lasted? My dad worked for the Texas Highway Department and continued to work. I would appreciate everything you could find.

— Connie Fuller

Coronavirus has been compared to various flus; what about polio?

— Jo Myler

The first polio epidemic hit Texas in 1937, and the disease circled back in 1942. “Polio flourished in wartime and post-war Texas,” said Heather Green Wooten, Ph.D., author of “The Polio Years in Texas: Battling a Terrifying Unknown.” From 1943 to 1955, “Polio raged throughout Texas with epidemics occurring somewhere in the state almost every year, often in several communities at once.”

From nearly 1,000 cases in 1946 to about 4,000 in 1952, Texas continually ranked as one of the highest in the nation in terms of polio incidence.

The first polio vaccine wouldn’t be approved for widespread use until 1955, so families had to white-knuckle their way through the polio epidemics the way we’re coping with COVID-19 —taking precautions and hoping for better days ahead.

“Communities reacted with dread because no one understood how or why people got (polio), and because children were the most frequently affected,” says the “American Epidemics” section of the Smithsonian Institution website, amhistory.si.edu. About two-thirds of the sufferers were children, and the rest were mostly young adults. While some survived unscathed, others were left without the ability to walk, sit up or even breathe unassisted. Five percent of afflicted children died, and the case fatality rate was much higher among adults.

In San Antonio, the polio season began in May. By that time, it was known that polio was caused by a virus but not how that virus was transmitted from person to person.

Because there were so many mosquito-borne illnesses — malaria and dengue fever were routine summer visitors in San Antonio and South Texas — it was hypothesized that they also might be the cause of polio, one of the reasons that many people who were children in that era remember trucks fogging the streets with DDT in the evenings.

Likewise, since rats helped spread typhus and bubonic plague, rodent eradication was a sign of springtime in the polio years of the 1940s and ‘50s.

Not for the squeamish: Polio wasn’t caused by junk piles, rodents or insects but by humans. It’s spread through fecal contamination of food or water consumed by the victim.

The first reported case of the year was also its first fatality, a 16-year-old boy who died at Robert B. Green Hospital on May 7, 1946, days after his doctor diagnosed him with “ascending paralysis,” a symptom of polio. That doesn’t mean his was actually the first case, since polio was rarely diagnosed without paralysis, and illness and even deaths were ascribed to other causes, such as viral pneumonia.

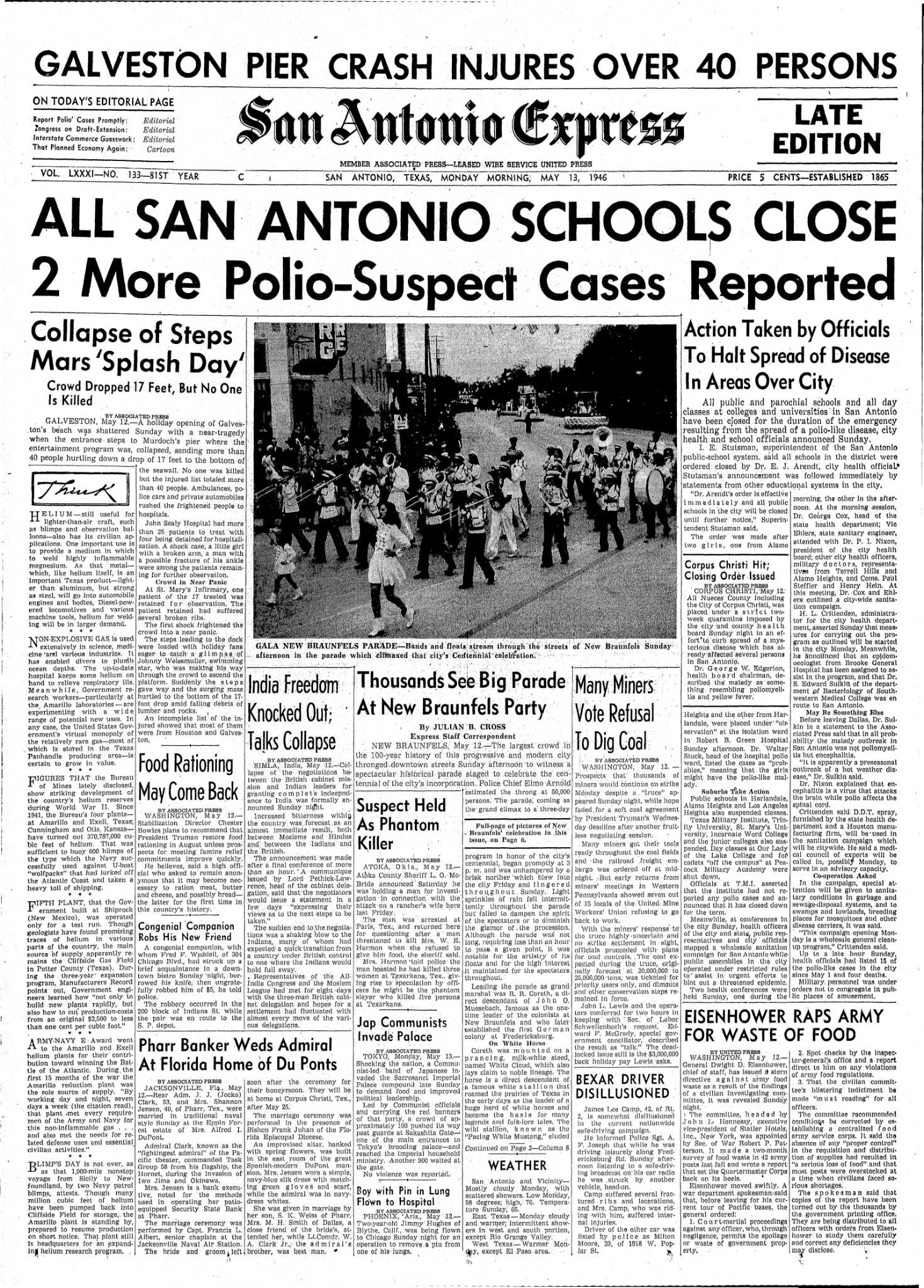

In the first week, there were 14 cases and four deaths. The city Board of Health moved to close schools, parks, swimming pools and dance halls — in some cases, only to people under 21 — prohibited the sale of unpasteurized milk and discouraged tonsillectomies at this time. Picnics and parties were discouraged, and a “war on flies” was launched.

Military personnel were forbidden to attend theaters, night clubs, social functions, church services or any other gathering open to the general public in or around San Antonio. Fort Sam Houston closed its theater, chapel, kindergarten, boys club and officers club. At Kelly Field, civilians other than dependents or employees were denied entry.

Because most of polio’s victims were young, “Public health officials didn’t advocate total quarantine of all nonessential businesses,” just the public venues where large groups of youth might gather, said Wooten, visiting assistant professor of History of Medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch-Galveston. “Overall, economic risk was not a consideration. Polio epidemics did not last for extended periods of time. It usually entered a community, struck with a vengeance, and then dissipated within a few weeks.”

Stepping up the clean-up campaign through May, the city added garbage trucks and hired a Houston company to spray dumps and cesspools with DDT, in case the disease was spread by mosquitoes. At this time, the city still had a lot of outhouses (outdoor pit toilets), over which there was some hand-wringing. But no action was taken.

As the cases began to multiply all over the state, leaflets from the Texas State Health Officer were distributed in cities and towns, with messages similar to what we’re hearing now, including “Reduce all human contact to a minimum” and “Wash hands thoroughly.” Popular entertainer Red River Dave McEnery sang “The Polio Song” over WOAI radio, exhorting listeners to “Keep the ashcan covered, never drink out of a stream./Take care that all the food you eat and kitchen ware is clean.”

San Antonio was identified as one of the hot spots of the disease in Texas, so hotels, though still open, were all but empty. Late-spring and summer events — graduations, league softball, horse and dog shows, the circus and club and business meetings — were canceled.

After the first round of health improvements and restrictions, some San Antonians took charge of their own safety. You could buy DDT sprayers or sign up for a polio policy that covered the insured for hospitalization and a private nurse. Families who could afford it bought train tickets to send mothers and children out of town for the duration, most often to Houston or to Port Aransas.

Meanwhile, polio victims — a few each day — ranged in age from a 10-month-old girl to a 31-year-old wife and mother who died in an iron lung. They came from Olmos Park, Alamo Heights, Highland Park, West Commerce Street and all over town. Except for servicemen, who went to Brooke Army Hospital, those who needed hospitalization went to the polio isolation ward at public Robert B. Green, where there was specialized equipment and nurses specially trained in polio care.

Cases were still ticking up steadily four weeks after the May 12, 1946, start of the lockdown, when San Antonio “popped the cap” on the polio ban for people over 18, and “soldiers and civilians crowded into nightclubs, bars, cafes and theaters,” as reported in the San Antonio Light, June 9, 1946. A month later, a Methodist minister and the owner of Playland Park were arrested for respectively allowing children under 14 to attend Sunday School and opening the amusement park to children of all ages for July 4, 1946. The charges were later dropped.

But most churches and businesses followed the restrictions. Churches held radio services, and the San Antonio Council of Churches cooperated on a weekly KTSA radio Sunday School of the Air. Children’s departments in department stores went to a telephone and mail-order business model. The ban continued more or less on an honor system, with Playland Park going full-blast through peak polio season, the ignoble exception.

The last polio patients of that season at Robert B. Green were discharged Aug. 30, 1946. The season’s toll was 113 reported cases and 13 deaths.

historycolumn@yahoo.com | Twitter: @sahistorycolumn | Facebook: SanAntoniohistorycolumn

"Shut" - Google News

May 10, 2020

https://ift.tt/2WHIcgA

Much like COVID-19, polio shut down schools, public places in 1946; officials urged hand washing and social distancing - San Antonio Express-News

"Shut" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3d35Me0

https://ift.tt/2WkO13c

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Much like COVID-19, polio shut down schools, public places in 1946; officials urged hand washing and social distancing - San Antonio Express-News"

Post a Comment